A Sense of Place

Indigenous architecture is about the honesty of a building, the materials used and the stories it tells.

BY Meghan Robins

Above the main entrance to The Museum at Warm Springs, the word “Twanat” is carved into black granite, which loosely translates as “to follow” in Sahaptin, or Ichishkíin S í nwit, the language of the Warm Springs Tribe. A stream graces the entryway, ensuring that water is the first and last thing visitors experience. Curved rock walls guide you toward thick metal doors decorated with a bronze sunburst handle. Every detail of the building is intentional: the size of each space, the materials chosen and the texture of light.

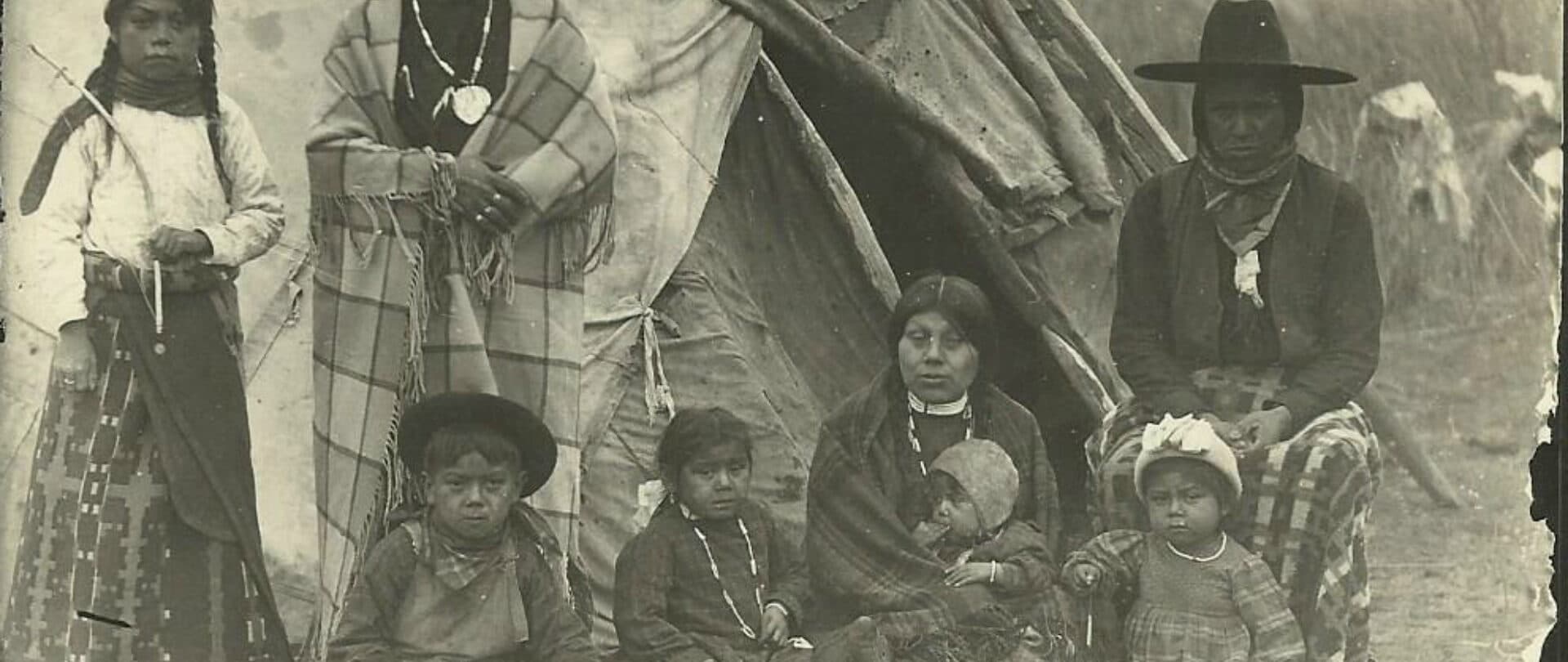

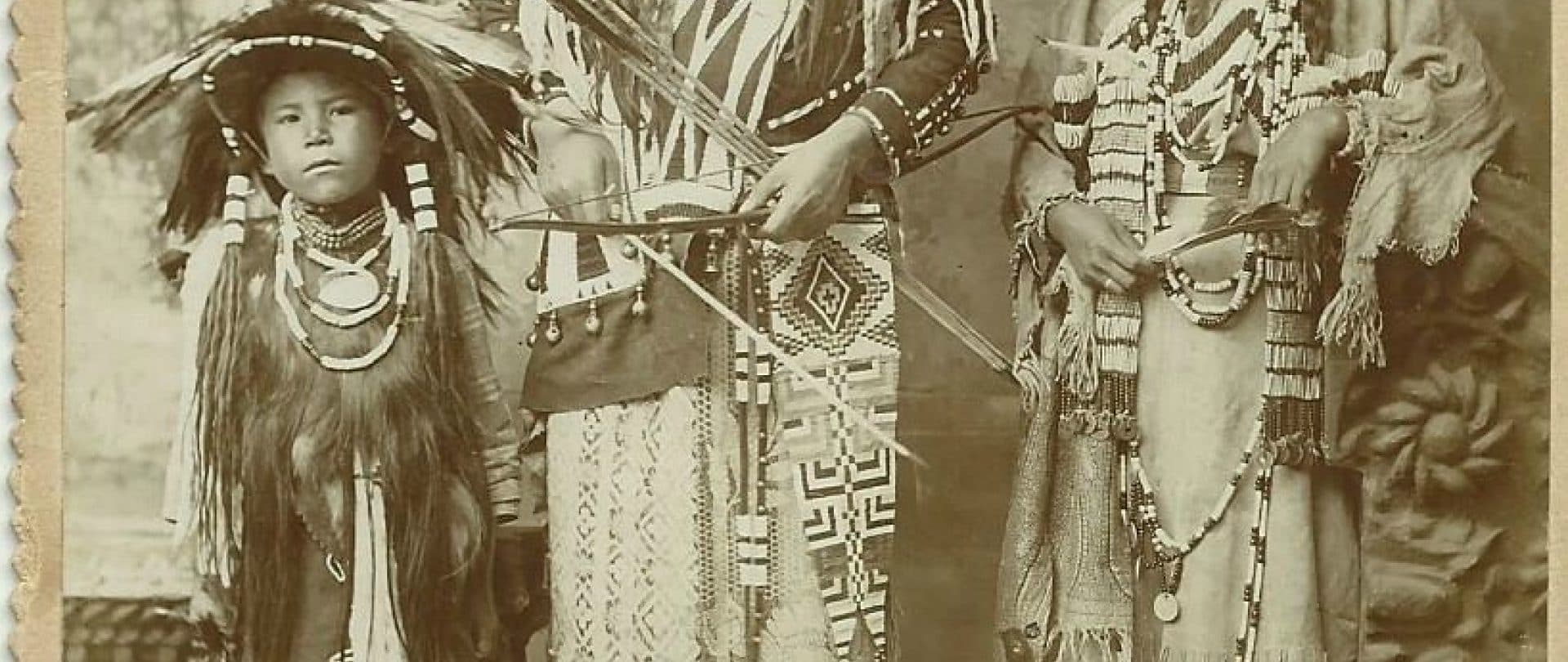

The idea of creating a museum owned and operated by The Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs began in 1955 during the 100-year anniversary celebration of the Middle Oregon Treaty signed in 1855. Onlookers and collectors offered to buy traditional regalia and other heritage items at the anniversary. Elders decided a place was needed to protect their communities’ heritages, histories and materials on their terms.

The Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs comprises the Wasco, Warm Springs and Northern Paiute Nations. From time immemorial, the area now called Central Oregon has been the traditional lands of the Wasco and Warm Springs Nations, with crossover from many neighboring nations. The Wasco People living along Nch’i-Wána, meaning “Big River” (later renamed Columbia River), were principally fisher-people who traded things like root bread, salmon meal and bear grass for other types of roots, beads, game, clothing and horses. The Warm Springs people migrated along Nch’i-Wána tributaries, moving seasonally between summer and winter residences while following game, fish spawning and specific roots and berry harvests.

By signing the Treaty of 1855, the Warm Springs and Wasco Nations relinquished approximately 10 million acres of traditional homelands to the United States Government, who sold it cheaply to incoming Euro-Americans through various land acts. In 1879, 38 Northern Paiutes were forcibly moved from the Yakama Reservation to the Warm Springs Reservation, creating what is now called The Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs. Today, a scant 644,000 acres make up The Warm Springs Reservation. Preserved in the Treaty of 1855 are Indigenous rights to harvest foods, fish and game throughout their greater original homelands. Additional sovereign rights not mentioned in the treaty also remain intact.

In 1960, The Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs began allocating funds to purchase heritage objects and reduce outside sales and cultural appropriation. Creating a safe place to house traditions and histories became critical. “We are the first tribal art museum in Oregon,” explains Executive Director Elizabeth Woody. “They identified the specific need to show our history and sovereignty by preserving and collecting tribal heirlooms and artifacts.”

Several lost and stolen items have been repatriated and returned to The Museum at Warm Springs, items that have been scattered across the globe to faraway places like Russia, Canada and Great Britain by fur traders, early colonizers and modern-day collectors. Such items hold great value and are often used during celebrations of major life events like births, deaths, naming celebrations and graduations. When the U.S. government systematically burned villages and forced Indigenous people to march for hours, sometimes days, forcibly relocating them onto reservations, even the wealthiest community members were reduced to bringing only what they could carry. This loss of material wealth, loss of land wealth, loss of religion, language, agency, and life was intentional, for it reduced great nations and exploited the mineral- and material-rich, cultivated land of the Pacific Northwest.

“Repatriating traditional objects means returning items to Indigenous nations, which are still recovering from these atrocities. In fact, we are all still recovering from these atrocities committed less than 200 years ago,” says Woody. “To have a tribal museum house artifacts that is built to Smithsonian Institution standards means not just having display areas but having a kind of conservatory. A place where we can repatriate and receive repatriated items from any institution in the United States. The Wasco Tribe is unique in the world in terms of the things they make. Incredible carvings are considered some of the world's best and most well-thought-out sculptures. These things were taken during the fur trapping time or older, depending on the trade. It’s an accomplishment to repatriate these items that have been retained and upheld by The Museum.”

While its nonprofit programming depends on funding, technical capacity, and staffing, The Museum at Warm Springs hosts year-round events open to the public, like master artist workshops, cultural talks and permanent and rotating displays. It is also where Tribal citizens hold meetings, host dignitaries and senators, and introduce people to their community. “We also need to provide positive experiences for children,” says Woody, “so they build respect for the diversity of peoples and understand that they are going to be in charge of their community someday.” This invitation includes school classes on and off the reservation. Throughout 2023, The Museum at Warm Spring has been celebrating 30 years (1993-2023) with special programs, an anniversary exhibit, several traditional master arts classes for the Warm Springs community, and a gala fundraising event that took place at Tetherow in Bend. The “30th Annual Warm Springs Tribal Member Adult and Youth Art Exhibit” opened November 1, 2023, and will be on view through January 13, 2024, which will cap off the anniversary festivities.

Indigenous Architecture & Thoughtful Design

In the 1960s, The Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs observed their old ways and language were disappearing with each new generation which became the impetus to build a museum. They began acquiring a vast and ever-growing collection of heritage items that needed a home, and in 1989, the Tribes hired Stastny & Burke Architecture in Portland to design a museum.

Architect Donald Stastny was a boy scout in 1957 when his troop traveled by train from Oregon to Pennsylvania to attend the Boy Scout Jamboree at Valley Forge. “As we went across the nation, where we’d stop, the boys would put on their regalia and dance. That’s where I learned to dance … on that trip,” says Stastny. This began a lifelong interest in and reverence for Indigenous architecture and design. Years later in 1988, Stastny was recommended by a fellow architect to bid for the museum design with The Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs. “There were very few tribal museums at that point, and those that were built did not necessarily create a prototype for Native American architecture,” says Stastny. “When we sat down with the people at Warm Springs, we were not given any particular direction. So, we approached it by asking, ‘What do you want a visitor to feel like? What do you want the takeaway to be for a visitor who comes to the museum?’”

They set up a studio on the Warm Springs Reservation and invited Tribal citizens to come by and talk, mostly listening and learning the value of storytelling. For example, “One lady started talking about her favorite type of rock, those found in streams weathered by water running over them,” says Stastny. “We asked the counselors what does this mean? They said it was a message that you should build out of real materials. Materials have permanence and it matters where they come from. So, throughout the museum you’ll find stone and bricks made from clay, metals that comes from the earth and wood that comes from Douglas firs and junipers. You won’t find plastics or synthetics.”

It was important to the elders that all three tribes were represented. “They wanted a place that symbolizes them as separate but confederated,” says Stastny. “When you look at the building, you’ll see a longhouse for the Wasco Tribe, a teepee for the Warm Springs Tribe and a travois for the Northern Paiutes, which is a French word for the device dragged behind horses by nomadic people.”

Understanding Indigenous architecture was a pivotal turning point for Stastny, who continues to design buildings with intention, thoughtfulness and honoring cultural traditions. “Indigenous people have an understanding of the spatial constructs. They are affected by what the space does. For instance, we developed a very strong rhythm going through the building, where it’s compressed or has low ceilings and then bursts out into larger spaces.” These spatial constructs, he explains, resemble the sequence of a dance.

To enter The Museum, one must go through a big stone drum, which represents the drum that sets the heartbeat. This low vestibule then bursts open into the main hall filled with natural light and supported by tall wooden posts and beams, representing the native cottonwoods surrounding the area. “The honesty of a building,” says Stastny, “is about how it’s made, how it’s supported, what the structure is, what the skin is. That’s what we really began to understand as we made the museum.”

Woody explains that the structure and materials used are critical to interpreting The Museum: “It’s strongly tied to the landscape of Eastern Oregon. The natural rocks, the wood structure, our long houses and big houses —are all tied to our sensibility and aesthetic as a people. We are part of this land, and the land is part of us. It gives you tactile sensations. It gives you the textures. It gives you the colors, and most importantly, the light.”

Because natural light has the tendency to degrade prized artifacts, it is often avoided in museum design. But The Museum at Warm Springs is full of light. And letting in the light is being discussed by others like the High Desert Museum in Bend, which plans to redo one of their exhibits specifically to let in more light. “Light is elemental to our culture and belief systems,” says Woody. “Illumination, being warm, many of our songs speak of light, being lit up, and how we are all light and water.”

For Stastny, the texture of light has transformed the way he looks at and designs most spaces. “Light and the effect it has becomes a very important part of architecture,” says Stastny. In The Museum at Warm Springs, “You’ll see examples of structure and how light is introduced into the building. We even set up the main exhibit area to have natural light coming in if the designers want to, or they can opt for more of a closed environment in there.”

Other elements connecting the space and people to the land include ash wall paneling framed in juniper. “Which is kind of unheard of,” says Stastny. “At the corners where pieces come together, we developed little bronze wraps that have the same effect as if you were tying them together with leather. Small details like that are all throughout The Museum. When you look at the building and live with it, you understand that is really a special place.”

But, says Woody, “The Museum is just a building. The culture and community are what makes it a bright light for the Tribes and other people who are coming into awareness about the history in the Pacific Northwest. It's often brutal, but we continue to carry on our traditions, despite laws that prevented us or prohibited us from speaking [our] own languages and practicing our own religions.”

Through its structure, thoughtful design and meaningful use of materials, The Museum at Warm Springs honors the people of Central Oregon, their relationship to the land and the storytelling that is vital to the area.

Visit The Museum at Warm Springs, located an hour north of Bend on Highway 26. Check their website (museumatwarmsprings.org) for hours, event details and current display exhibits. When you arrive, notice the sounds of Shitike Creek flowing nearby, the rustling cottonwood groves, and admire the natural trails and shrubbery and how the building itself fits thoughtfully into the landscape.

You May Also Like

Food + Drink

Home Is Where The Food Is

Food + Drink

Redefining Farm-to-Table

Art + Design

Where Artists Collect

Art + Design

DIY Cave

Local Vibe

Music Vibes

Environment

Epic Hikes

Environment

Off The Beaten Path

Environment