All in a Life's Work

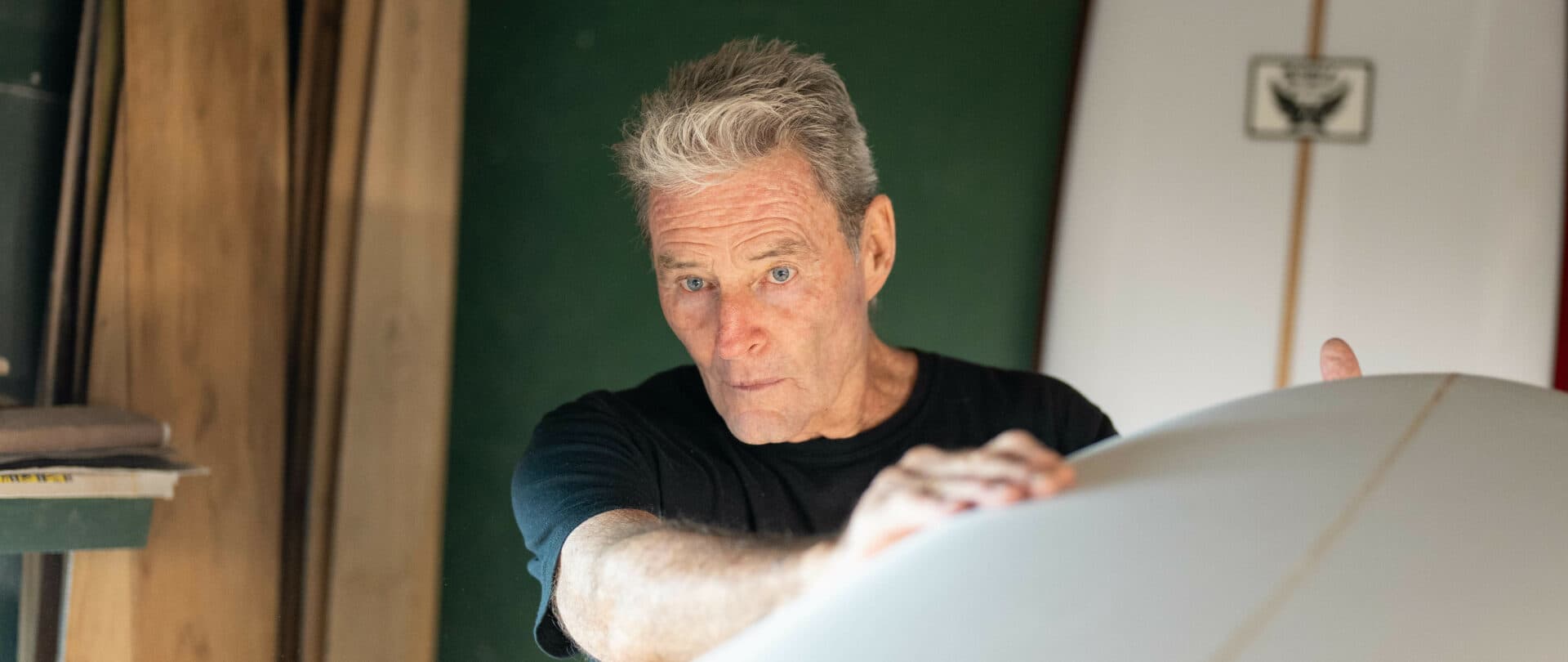

Mark Angell: Surfboard Shaper Extraordinaire

BY Mary Troy Johnston

After five decades of shaping surfboards—over forty thousand boards since he last counted eight years ago—Mark Angell has never veered from the current that moves his work. Over and over and over again, with an individualized result each time. And, that’s really important to surfers who are serious about their sport. Many have a variety of boards in their quiver to be prepared for ever-changing conditions. Someone with Mark’s expertise can craft just the right board.

Surfing and shaping surfboards has been his life’s work. He holds the world’s record for the longest nose ride for 39.6 seconds, a feat he accomplished at the Cowell’s Beach noseriding competition in 1966. Mark has built on that record replicating the longevity in his craft.

While the industry has gone in the direction of computer guided, machine shaping, implementing the specifics of a CD, Mark has continued to hand-shape each of his boards. He starts out with a blank—a prototype of a board—which he eventually carves and planes into a customized product that represents the understanding achieved between the shaper and the surfer about how the latter wants his board to perform in the water. One of his favorite tools is the Skil 100 Planer. A surform, hand planer, sanding block and sandpaper are also in his toolkit. With the knowledge and experience he has accumulated over time, he sometimes feels the tools are intimate expressions of his craft. He utilizes a template he creates, an overlay that enables him to get the right measurements. He must have had an inkling early on that he would be shaping boards for the long-term, because he saved his templates back to the 1960s.

Styles of surfboards come and go, and then come back again. He has worked with surfers who want a retro-style board and it’s easy enough for him to resurrect a template, perhaps one he has saved for six decades, something that has not seen the light of day for no telling how many years. Once he finds the center point, he begins to look for the wide point. He also searches for the spot one foot from the nose and another one foot from the tail, making all the critical marks with a pencil on the board. He uses the marks to put the template in the right place, then the shaping begins. He takes the board down to the desired thickness, which partly depends on the weight of the surfer. He has to make decisions about how much lift to give the nose or the tail. Mark explains that if “you put an extra half inch in the front or the back” of the bottom curve, you can create a “pendulum effect.” You can increase the pendulum effect in the back and “lift the whole thing up an inch or two.”

The years and years of shaping have not only contributed to technical expertise; they have sharpened his vision. He says, “There is a pre-plan.” Upon seeing the blank, he can visualize “what [he] wants out of it,” and/or “what needs to be done.” He relies on his sense of hydrodynamics, which, as an avid surfer, he still hones today. He also recognizes the visualization of the form as a creative process, and the process itself, as similar to sculpturing. The interaction with the surfer for whom he is making the board is also very important. He routinely asks, “How good of a surfer are you?” That way he can figure out where the surfer is on the learning curve and individually tailor the board to that particular experience.

Back in the 1970s, legendary surfer Michael Ho asked him to shape a board. Mark recalls the beach on O‘ahu where he was sitting in a bush and watching the professional surfer ride the board he had designed. When Michael returned to the shore and said it was the best board he had ridden, Mark could barely believe it. Consequently, other pros came to him for their boards.

Mark reminisces about having worked with the best shapers in the world. The ever so fond memories are now shadowed by sadness because many of them have passed. In particular, he remembers shaping boards alongside Dick Brewer and Mike Diffenderfer. Mike died in 2002, and Dick recently in 2022—their legacies well-established. Dick’s boards have been called “revolutionary” and Mike lived up to his reputation as the “Michelangelo ofShapers.” Mark recalls how he shared a shaping room with Mike for seven years in Hale‘iwa on the North Shore of O‘ahu and how he was “so honored to be a part of the realm.” Mark misses the camaraderie of the shapers he has worked with in the past and also the vibrant shaper community on O‘ahu, with whom conversations flowed non-stop about the cutting edge of design.

Mark has had such a long ride with so many stories to tell and experiences to share. The gas station where he got his start back in 1964 was located on the beach in Santa Cruz. Called Otto’s Fun Spot (named after the owner), it rented a variety of items to residents and visitors alike, including surfboards. Otto’s wife did not want her husband to work with fiberglass or resin, so Mark stepped up. He remembers saying to himself about the owner, “Man, this guy is a character.” Once, as Mark and the owner stood talking, a car passed by, then a towel came flying off the roof and the car kept driving. Otto went to pick up the flyaway towel, saying he could wash it and rent it out. When it was time for Mark to move on, he had what he needed more than anything else—a Skil 100 Planer—to fulfill his future potential as a shaper, a surfboard builder.

When I spoke to Mark, I could not help but ask whether he believed in magic boards, as surfers dispute this among themselves. I thought if anyone had seen or heard about a magic board, it would be one of the most seasoned surfboard shapers in the world. He verified their existence and even said that once they had their magic boards, some of the pro surfers kept them on ice until the right competition and right conditions appeared. He called a few days later to say that he had thought about what makes a magic board and described synchronicity between the board and the rider, the performance aspect of the board becoming one with the physical effort of the surfer. When the magic happens, the board becomes an “extension” of the surfer.

Talking to Mark really gives you a sense of how surfing has changed. He describes the balsa wood boards so typical in the late-1950s. The main challenge with them was that when the board got a ding, it soaked up water. Those boards, which would cost between three and five thousand dollars today, he remembers as “lightweight, great and beautiful.” He expresses disbelief that surfboard makers used to resin them some “abstract color to cover up the wood.” He explains that around 1959, polyurethane foam started being used more extensively, and that a couple of companies started using closed cell foam, making it possible to get a ding and not absorb water. He has just finished building a few epoxy boards with carbon filler, emphasizing “they are really strong, yet they are light and responsive.” Mark still uses polyurethane and EPS foam for epoxy construction to make boards, saying they can break, do break and will break.

Mark describes wryly his rarefied experience, observing, “there are only a couple of us left doing the old school hand-shaping; we talk between us and realize we are a dying breed.” They certainly share a level of perfectionism. When I asked him if he were a perfectionist, he responds without hesitation, “If you are going to be doing it, you might as well do it right.” He adds that he cares about what is representing him. And, almost anyone who observes the grand arc of his stellar shaping career would add that he has got it near perfect.

Learn more at markangellsurfboards.com.

Destinations

Once the bubbling epicenter of life on Kaua‘i, Hanapēpē town has reinvented itself time and time again proving to be “the town that refuses to die.

Art + Design

Through her brand EHA Culture, artist Erin Hofmann fuels her passion by producing island essentials that are both fashionable and functional.

Food + Drink

The husband and wife duo bring Hapa PDX to Kaua‘i