Home Again

The sacred ground at Nu‘alolo Kai once again provides a safe haven for seabirds.

BY Mary Troy Johnston, Ph.D.

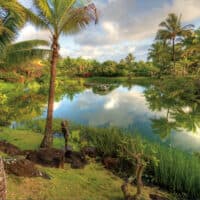

Nu‘alolo Kai on Kaua‘i’s Nāpali Coast is an ancient Hawaiian fishing village and a continuous civilization from the twelfth century. The present-day site of incredibly rich and diverse archaeological artifacts is home to a once thriving coral reef, playground for honu (turtles) and ‘īlio holo i ka uaua (Hawaiian Monk Seals) and lost home to an abundant population of seabirds. Evidence of how Hawaiians lived centuries ago has often disintegrated in such a harsh natural environment. The vast discoveries on Nu‘alolo Kai are a gift to Hawaiians who have lost much of their history. Preservation of the artifacts has been attributed to the “overhanging cliff” that shielded the site and the “heavy sea spray, which permeated the deposits with salt.” (Patrick Vinton Kirch, “Feathered Gods and Fishhooks: An Introduction to Hawaiian Archaeology and Prehistory”, University of Hawai‘i Press, 1985, p. 101) The artifacts revealed there were extensive and showed the activities of the inhabitants to be very specialized, complex and productive. The story told by the relics was also the story of a bird people. Tools made from bird bones were among the findings. For example, the residents crafted bird bones into sewing needles. The remains of the birds showed how plentiful they were, reminiscent of a time when flights of birds darkened the skies.

In old Hawai‘i, the birds were cherished as generous provisions of food and adornment, headdresses and capes fit for ali‘i (royalty). The ‘ahu ‘ula (cloak) and mahiole (helmet) artfully worked in feathers were stunningly attractive and provided spiritual protection for the wearer. Birds were essential to Hawaiian fishing villages. The fishermen worked in tandem with the feeding birds, following them to locate the catch. In old Hawai‘i, humans had a shared existence with nature based on mutual dependence and respect for their shared destiny.

The balance between birds and humans was disrupted with the introduction of mammals, of which there were none, except the Hawaiian Hoary Bat. When rats, feral cats, feral pigs and barn owls began to populate, seabirds were an incredibly vulnerable and delicate prey. Many seabirds lay one egg during nesting season, presenting a tasty morsel to predators. Furthermore, chicks are small and edible, as well as small adults typical of some species. Science Director André Raine for the Archipelago Research and Conservation LLC outlined the consequences of predation at Nu‘alolo Kai. Some species became extinct, going the way of approximately thirty percent of seabirds. Some of the remaining seabirds sought refuge away from predators on Nu‘alolo Kai. According to André, several suffered a “huge range contraction.”

The conservationist further describes the current state of affairs with seabirds that traditionally made their home at Nu‘alolo Kai. André says that there is a “good population” of akē ‘akē (band-rumped storm-petrel), although they are now restricted “way up into the cliffs,” making the species very hard to study. That is also true of a good population of endangered ‘a‘o (Newell’s shearwater) that took to the cliffs. Another species, ‘ou (Bulwer’s petrel) has not been identified yet as returning. Its small size makes it especially prone to predation. A cause for excitement is that the ‘ua‘u kani (wedge-tailed shearwater) has been recorded as making a return. The first nest was detected in 2021, and the first chick fledged in 2022. Excitement grew as the next year, there were five chicks. There is great expectation that having them back in a safe place will increase numbers quickly. André makes it clear that they are not endangered, but they have elsewhere been tragically “killed in the hundreds” by predators.

Part of the strategy for preparing a safe home for the returning birds has been to make marine plank nest boxes to give the seabirds a head-start in nesting. The nest boxes have a tunnel where the bird can enter a relatively safe environment. They are located on top of the ground and rocks are arranged around them to anchor the boxes. As Nu‘alolo Kai is sacred ground, volunteers are careful not to disturb the ground. Nest boxes offer several advantages. As some seabird species spend several years digging a burrow for a nest, the nest box will save a lot of time. The more controlled environment allows scientists to collect and feed data into assessment programs. Notably, students at Island School took part in the project by painting the nest boxes. André noted how important it is for community members “to connect with the natural environment” so they become more closely bonded with creatures usually out of their realm of experience. Volunteers for the Nā Pali Coast ‘Ohana, an organization that stewards this wahi pana (celebrated place), have been removing invasive plants for years and replanting native plants. They will eventually do this next to the next boxes to provide shade, enhancing the suitability of the nesting spots even more.

Before Nu‘alolo Kai is ready to host the return of seabirds, predator control needs to be more complete. Kaua'i-based Hallux Ecosystem Restoration LLC has the contract for Nu‘alolo Kai. Much has been accomplished and upon completion, a sound system consisting of bird sounds that mimics the scene of robust avian activity has been engineered to play at night when the seabirds return from sea. It is designed for social attraction as an invitation for the seabirds to return. It has yet to be fully employed until the rats are fully under control, but it has been tested early, attracting some circling birds. At Palmyra Atoll, midway between Hawai‘i and American Samoa, a seabird restoration effort in 2020 also utilized a sound system, nicknamed by researchers “seabird discotheques” that played recordings of bird calls from eight species that had long been absent from that location. (“Seabird Attraction Succeeds at Palmyra Atoll”, 22 May 2023, The Nature Conservancy, nature.org) Several years later, the presence of several Pākalakala (gray-backed tern) promised success. The researchers at Nu‘alolo Kai also feel they are turning a corner with their efforts and are looking forward to the impact of an increasing seabird population on the ecosystem's health. In addition to saving birds, they value being a part of the cultural revival symbolized by helping to return Nu‘alolo Kai to its natural state of abundant resources.

The story of the chain of effects of seabird guano (excrement) provides insight into a complex ecosystem with land and sea, creatures in the sky and under the water, flora on land and in the ocean, all tightly bound together in a network of connectedness. Seabirds travel far out to sea to feed on fish. For example, the ‘ou (Bulwer’s petrel) has been known to travel over a thousand miles searching for food. The fish diet is rich in nitrogen and phosphorus. As a result, seabird guano also becomes rich in these nutrients. When the seabirds return to land for breeding season, the guano they deposit nurtures the soil and supports the growth of plants. When the rain produces run-off, the guano goes into the sea. Scientists have realized that the nutrients good for plants are also good for coral reefs. This is nothing short of amazing news for troubled coral reefs and at risk of surviving. The coral reef protecting Nu‘alolo Kai from ocean swells and providing a habitat for ocean life has been a grave concern as it has been steadily dying. The prospect that guano from returning seabirds may benefit the reef in years to come could not be timelier. The run-off of nitrogen and phosphorus feeds the algae, which helps the reef grow and become more resistant in case of a future bleaching event. In turn, it feeds the zooplankton that different forms of sea life depend on. Ideally, fish grow bigger, and the fish population becomes more diverse. The cycle continues as more fish are consumed by more seabirds and produce more guano, potentially offering a way out of the cycle of destruction of the coastal ecosystem. This natural process is linked to a feeding event in the far parts of the ocean, which has efficacious effects on the land and coast so far removed. This realization is a cause to rekindle our respect for nature and return to the natural wisdom of ancient Hawai‘i as the seabirds return home.

See + Do

See + Do

Eat + Drink

See + Do

See + Do

See + Do

See + Do

See + Do

See + Do

See + Do

Eat + Drink

See + Do

See + Do

See + Do

See + Do

See + Do